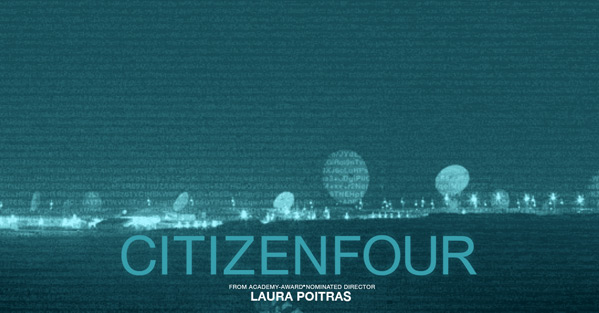

Interview: ‘Citizenfour’ Director Laura Poitras on Storytelling in Docs

by Alex Billington

December 19, 2014

One of this year’s must see documentaries is Citizenfour, directed by Laura Poitras, an inside look at the story of whistblower Edward Snowden. Poitras was contacted by Snowden early on and was right there with him, filming the entire event, as he leaked the information from Hong Kong about the NSA’s spying program that stunned the world in May of 2013. Poitras has made two other provocative docs previously, The Oath and Flag Wars, and she’s back with another one that is a bit more intimate, but still as powerful. I raved about Citizenfour after catching its premiere at the New York Film Festival, and I met up with Laura for an interview in New York City. What follows is a fascinating discussion about the power of storytelling.

I wrote in my NYFF review, «The film exceeds on all levels because it is so expertly made by a filmmaker who can balance humanity with reality and storytelling. Director Laura Poitras takes the news and shows us the people behind the news, giving us a fascinating, jaw-dropping inside look at moments when history was made.» She emphasizes the journalism and thoughtfulness of humanity over the intensity of the media, and it’s rather moving to witness. This was my first time meeting Ms. Poitras, and I wanted to talk to her about Snowden, and how she best captured him, and wanted to portray him in this doc. We sometimes disagreed, but no matter what it was still an invigorating and exciting discussion, and I’m proud to present for reading.

For more reading on Poitras — click the image above, from NY Times’ profile in 2013. Click the other below.

I started out with a lighthearted question about if she hears a lot of questions that she isn’t expecting because she has been out touring with the film and doing so many Q&As.

Laura Poitras: There seems to be certain tracks that people go down. And then sometimes people are like, «Oh, there’s fresh snow over there. Let’s go that way.» But it’s actually totally a surprise. There’s a transition between the sort of more creative process and then you realize that there is this kind of consistency of questions, but you never know what they are until you start to get asked them. Then it’s always interesting to know if the film just begs those questions or if they become self-fulfilling. You know, like, «Oh, well this person asked…» You know, we’ll go down this path because somebody has cleared the way down that one.

With this film specifically, I feel like there’s already preconceived notions people are bringing to it before they see it and then they’re being changed through the process of seeing it. How do you react to watching that happen as the filmmaker?

Laura: The most interesting thing in terms of the response of the film – I think people really enjoy seeing the journalism behind the scenes. There’s something about that and the… It’s not just, I mean it is a story. Hopefully in 20 years you can play it in whatever device will exist in 20 years and you’ll hit play and hopefully the film has enough information were you don’t need to know much else.

But because of the current context, people follow the news. And so, they are bringing their relationship to some of the events that… It’s kind of like if you use a well-known song that people have played in your movie, people will hear the song, but they are also going to associate it with a bunch of other memories because they know the song. They take their memories into the experience.

I think that there’s something a little bit like that with the film, because a lot of times people remember that they’d seen that published in The Guardian, the video interview. Not everybody has seen it, I’m sure. A lot of people never saw it. But a lot of people did see it. Not all the people I’m talking to saw it. So they are maybe following the stories unfolding, so they have their own, in a sense, narrative of Snowden. Then they are getting a different version of it with the film. So the film hopefully stands alone, but also it’s standing in dialogue with people’s own relation to Snowden and the revelations. So there’s a kind of rift that happens.

This is an odd question, perhaps, but: was there a goal you had with this film? Or is there a goal you hope it achieves? Do you hope it goes out and changes the world, or was it purely your goal as a filmmaker to capture something as best you could and put it put there?

Laura: Really, to be honest, I put myself in the category of ‘filmmaker artists‘. And in that category, it’s about communicating something. So that’s the goal – it’s the work. It’s not like the goal is to get other people elected in Congress. I don’t make films that are goal oriented outside of the films. So the goal is ‘the film’, to take you on a journey and hopefully change you in a way because you learn things or you are exposed to something [while watching the film].

Like you when read a good novel. So you wake up the next day and you are still thinking about it or it resonates. To me that’s the goal. Like, a work that stays with you. But of course I’m trying to express things about the world. I definitely feel that the country is veering in some dangerous directions and I want to say something about that. I think we’re living in a bit of a moral vacuum right now in the United States and I think that that is problematic. So I want to say something about that. I’m trying to express things about the culture right now as a US citizen. But it’s really about trying to say something about it. It’s not like I think that a film is going to change… you know. I don’t think films or art should be undertaken with some motive outside of their medium…

Out of creating art, in a sense.

Laura: Yeah. But art goes a long way, too. If you look at [George Orwell’s] 1984, which I reread, that’s a great book. I reread it and it’s a great book because it’s a great book. It’s a book about portrayal. It’s about a Dystopian future. Did Orwell create it… Of course, it’s also a warning sign. But it functions on its own terms, right? I think that good art should do that. Good storytelling should do that.

I agree. So then my next question is, how do you provide some sort of optimism, especially with the way Citizenfour ends – you know, it’s bigger than Snowden. There’s more…

Laura: The optimism, to me, in the film is… it’s certainly not the state of our government. That’s not the optimism. The state of our government is not so great. We’ve been at war for too long. But I think the willingness… that people are willing to take sacrifices to expose things, I think that is actually optimistic. I don’t think that that position is held only by Snowden in the film. I think also with William Binney. And then I would say Glenn [Greenwald] represents that and Jeremy [Scahill] represents that, and hopefully the film represents that. There are things that are happening that are wrong and they should be challenged.

And I’m not that shy about saying that. I don’t think we should engage in that kind of…

That almost gets back to the goal — does the documentary almost say you should go out and be a whistleblower, but don’t forget there are some concerns…

Laura: No. I mean I’m definitely not trying to say that. What I’m saying is: why do we live in a society where these risks have to be taken so we can understand the fundamental things that we should know as citizens? Like, this is our country… We don’t live in a monarchy. We live in a democracy. There should be transparency and these kinds of things shouldn’t happen in secret. So the goal isn’t — let’s have more people who put their lives on the line.

But it is a positive sign that people are resisting… or dissidence… or whatever you want to call it. They’re saying that in the face of seeing wrongdoing or something that they feel is problematic that people will stand up and say, «No, this isn’t right.» And that will, in many cases, come with potentially really negative consequences and potential repercussions.

In terms of the film, the structure of the film, I don’t know if it’s to create optimism, but I definitely didn’t want the end of the film to feel like there’s resolution. I wanted it to be unsettling so that the audience would be left with not a narrative that ties up all the loose ends, but one that pushes it outside of the frame. Because I think that the things that motivated Snowden to come forward, that motivated William Binney to come forward, are still ongoing.

So even though in a sense you get a narrative arc where William Binney, at the beginning of the film, no one is paying attention. At the end he’s holding court before Parliament in Germany. The truth is that the policies are still in place. So, in a way, he is vindicated if you want to look at it in some kind of dramatic structure. You see a whistleblower who is kind of trying to warn people where no one is paying attention, and at the end you actually have a world that does pay attention. So, in a way, it’s a happy ending for him. On the other hand, the policies are all out of place. So you shouldn’t feel good about it. I think it’s good that we know more. But with that knowledge we have to do something. It’s not enough to just know what the government is doing.

Yea, this mirrors reality in the way that the film ends and there isn’t a real resolution yet, and here we are — the NSA still exists and not much has really changed yet.

Laura: I think it’s actually changed a lot. It’s changed the way people think. Not that many people can say they’ve done that. I also think there has been technological changes, and there’s been legal changes. Now that we have documents – there are court cases that are challenging these things that didn’t exist. That’s the scene at the beginning where you have this bizarre courtroom where the government is arguing, therefore they should bypass the judiciary. And now there are documents that actually say what the government is doing, those policies are being litigated and we don’t actually know what the end result of that will be.

How do you, as a filmmaker, work around some of the negative preconceptions of Edward Snowden? Did you approach it any differently in how you’re presenting him with your footage? Was there more footage of him you didn’t use?

Laura: I live in Berlin, so I have a different [view]… Actually, there’s a lot of public support [for him]. In terms of the question about Snowden, the answer is no, we didn’t set out to make a film to change public opinion. I don’t spend the type of time and take the risks that I do to try to tip opinion polls. That’s not what I set out to do. What I’m trying to do is tell something about the truth that I experienced and what I witnessed. Is that different than what the mainstream media portrays or what the Obama administration portrays? Yes, of course it is. But that doesn’t mean that I’m manufacturing a narrative.

In the cinéma vérité tradition of filmmaking, you film things as they happen. Then people can decide where they stand on it. But there’s a bedrock of, well, you get to know how people get to tick in a way in that kind of situation. And I’m interested in that. What I was interested in was the extraordinary circumstance that a source was willing to go on the record and allow me to film it. And so, that’s what I felt my job was to do, was to document the journalism that was unfolding. And you see the kind of progression that happens over a very small amount of time that had a major impact internationally.

I’m super interested in that. But I’m interested in that in a big picture, human drama sense of being interested. In other words, why would somebody so young risk so much? It doesn’t have to be about the NSA. It’s like – why would anyone risk so much? Would you risk so much? Would I risk so much? And then his choice to come forward was also so risky. This is a gamble where you go all in where if it doesn’t… you know, the stakes are really high. People could have not paid attention or somebody could have knocked on the door and stopped it all. Glenn and I could have been targeted legally. That hasn’t happened. There are a lot of risks that went with it. But I was interested in:

What is the culture that we’re living in where somebody is willing to take that kind of a risk?

Do you feel at risk in your own way? You’ve already poked at the government with your last two documentaries, do you think a third will poke them in a way where they’ll eventually take your passport and say you can’t come back? Is that a concern on your mind or are you purely about, «I’ve got to tell my story, it doesn’t matter what happens.»

Laura: This film came with way more fear than any film I’ve ever made. So I can definitely say that, and partly because I’ve done enough research in knowing about intelligence agencies to know how angry people were going to be about this. That was clear to me, if Snowden was legit that this was going to create some really powerful enemies. So it’s hard to just brush that off.

On the other hand, I still think that we live in a country that has a press that functions as a free press. I think that there are countries where this reporting – you do get a bullet in the head. Mexico, for instance. So I do feel like we still uphold that, and there’s been institutional support for the reporting that we’ve done, there have been news organizations that have recognized the reporting that we’ve done who would not allow certain things to happen.

On the other hand, I’m living in Germany because I was harassed at the border for so many years because I didn’t feel like I could bring source material across the US border, which isn’t to say that I’m not very aware that in this country we are going after people who expose wrongdoing rather than people who commit it. That’s been the unfortunate legacy of the Obama administration, is: how many people have been charged under the Espionage Act of whistleblowers, where nobody has been… There have been no investigations into who tortured people or those kinds of things. That, I think, is very troubling, kind of culture of secrecy and more on whistleblowers and more on journalists. I think it is real.

So, on one hand, I’m not going to say we’re living in state where there’s not a free press, but I think it’s being threatened.

Of course. And that’s why I wanted to ask, jokingly in a way, should I be concerned if I write a positive review of this film?

Laura: No…

Is it that much of an impact film? I don’t mean that seriously, but…

Laura: Listen. I don’t think the government is happy that this movie has been made that is being seen by lots of people and being, whatever, relatively well-received. I’m sure that this is not the narrative that they want to tell. But I don’t think that they’re going to… There’s no score list of who gave a positive review to add any kind of negative repercussions. We’re not living in that society.

But I do think that we’re living in a society where we do have a national security state that’s growing out of control. A lot of it is profit driven. It’s corporate. And it has self-interest to maintain its expansion, because it’s about money and it’s about power. And it is a powerful machine. And it’s a dangerous one. I’m on a watch list. I have no idea why and I don’t know how you get off of it. That’s a kind of creep society to live in.

No doubt you will receive some opposition, not from the government, but from some people who just don’t believe you. Not that I know anyone, but how do you respond to them? How do you respond to the people that say you are like Michael Moore telling a manufactured story?

Laura: First of all, I’m going to defend Michael Moore. I love Michael Moore’s filmmaking. And people always like to compare and contrast me and Michael. I’m like we have different voices, because that’s what you kind of want. You have writers who have different voices. You have filmmakers who have different voices. But ultimately, Michael is interested in making a good movie. Yeah, they are political, but he wants to take you… he believes in the power of movies and the cinema and he wants to tell a good story. Yeah, it’s about political things, but he also wants to make people laugh and other things.

First and foremost, we work in the medium of film and we have to succeed in the medium of film. It’s not the medium of opinion writing… Everybody who makes a film, the first thing you need to do is do good at your craft. But people have to their interests. So, yeah, I have a political interest. Michael has a political interest. So people have different types of things that drive them.

But I’m certainly not… And actually, I think Michael’s films are good stories. But I tend to make more open-ended films. So the film I made about the war in Iraq, I’m not shy to say that I was against the occupation of Iraq. I just thought the idea of occupying a country to bring democracy, those two things don’t go together and it was probably going to end badly. Which isn’t to say that I didn’t change my opinion about what was happening once I was filming. So I went in there skeptical about this whole project – bringing democracy to the Middle East through occupation, which I felt was tragic to begin with, but then once I got there and I saw Iraqis who were willing to vote, they were thinking about it differently. There were thinking about living under a dictator for 30 years and, actually «I want self-determination.»

So I had to sort of dial back some of my preconceptions because when you see people who are willing to go to a polling station and maybe be murdered; I don’t know that many Americans who would vote if there was a threat of violence that could lead to their death. A lot of us take our democracy for granted. We don’t vote. We’re lazy. Whatever. But when you see people who are denied self-determination, they will put their lives on the line. Iraqis were willing to put their lives on the line to engage in a political process. And so, I had to recalibrate my preconceptions to incorporate that, which doesn’t mean that I think the US occupation was well done, it was a good thing, but that you need to factor in what Iraqis wanted.

It’s kind of a long-winded way of saying that it’s not just about… as a filmmaker, I don’t want to confirm preconceptions. I want to actually arrive at a place that’s not the place where I began. And I want, hopefully, the audience does that, too.

But with a lot of things that I feel about America post 9/11, I do think that we’re in a moral vacuum in this country and that there are things that boil down to questions of right and wrong. In a democracy, should we have a government that is so secretive? I think that’s wrong. And I think we should say that’s wrong. And I think journalists should say that. And I don’t think that it means… I don’t know. I’m not trying to make propaganda. But I do think that at some point – there’s some things that are threats to democracy. And I think a lot of things that are happening in response to 9/11 are threats to our democracy. And I don’t think that it’s narrow to say that or that I’m trying to create propaganda. But I do think that there are real threats.

In terms of what’s in the film, of course we had to make decisions about… I’ve got hundreds of hours of footage, not all Snowden, but other material I had been gathering for many years. Yeah, we had to make tough calls. But there wasn’t a filtering really. One filtering that I would say is that there are still certain things, that – Snowden is still a source and I am still bound by some things I would describe as source protection related things. And I know that there is a massive investigation going on. So if the government asked me to subpoena my raw footage, I would say no, and they would have a fight and I would never hand it over because I have an obligation to the source. And I’m not interested in revealing information that helps the government with their investigation.

There are certain things I don’t talk about. I’m not going to talk about specific details about documents, because I feel like those are still things that I’m bound by certain confidentialities.

I understand. So the last thing I want to ask — what do you suggest, or what ideas might you have, to get more people into more documentaries? I always try but it’s not easy to get moviegoers to see documentaries, but there are some good ones. Once you see those, it’s like the whole door gets thrown wide open and they fall in love with more.

Laura: Ultimately, it’s about good storytelling. So we have to have filmmakers who are telling good stories. Again, Michael Moore is a good example of how you do it, like Bowling for Columbine, or Fahrenheit 9/11, it grossed $100 million, right? That means a lot of people went to the movies. So I think you have to tell a good story, ultimately.

I really love cinema. I love the experience of being in a room, in a theater, in a dark theater where you are having a relationship, where you are watching the screen, and it’s this private experience, but it also happens with other people around you. I think there’s nothing like it. And I still think it’s a very, sort of, American populist medium that is amazing. I particularly liked seeing Citizenfour with an audience. It’s great. We had done screenings before, but when we got to show it at New York Film Festival, it was wonderful to have that many people respond to the film.

I think these are films more than they are documentaries. I think documentary sometimes comes with a stigma that, «Oh, it’s going to be educational,» rather than, «I’m going to go and see a movie.» And I think maybe we could shift that a little bit. And I think certain movies do do that, like Man on Wire, which is just a great movie. Yeah, it’s based on… it’s nonfiction, but it’s a great movie because it’s a great movie. I think people will go to those. Maybe there needs to be more reaching out on social media and getting young people drawn in, different ways of drawing them into them.

Thank you to Laura Poitras for taking the time to speak with me, and congrats on the success.

Laura Poitras’ documentary Citizenfour is now playing in select theaters from Radius-TWC, so check your local listings. For more info visit the official website. Find my review from NYFF here. Thanks for reading.

Find more posts: Documentaries, Feat, Interview

1

DAVIDPD on Dec 19, 2014

3

SalsaBandit on Feb 25, 2015

New comments are no longer allowed on this post.

Текст выше является машинным переводом. Источник: https://www.firstshowing.net/2014/interview-citizenfour-director-laura-poitras-on-storytelling-in-docs/