Interview: ‘The Overnighters’ Director Jesse Moss Talks Making Docs

by Alex Billington

October 22, 2014

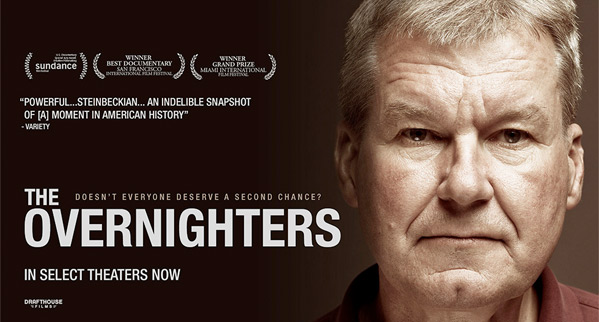

One of my favorite documentaries, in fact one of the very best documentaries this year, is one called The Overnighters from director Jesse Moss. The film follows a wild, almost unbelievable story set in North Dakota about a local Pastor named Jay Reinke who risks everything to help his new neighbors. It won over crowds at the Sundance Film Festival this year, picked up a Special Jury Prize, before going on to play at the Tribeca, Sheffield, Montclair, Sydney and New Zealand Film Festivals, winning awards at Full Frame, Miami and San Francisco, too. Drafthouse Films bravely picked up the doc and it’s now playing in select theaters. I was lucky enough to meet up with Jesse Moss for an interview in New York last week and it was wonderful.

We talked for nearly 30 minutes about everything from his own drive to make docs, to the openness of Jay Reinke, to the process of making a doc by himself, and getting the footage that we see in the film. It was an incredible, invigorating, fascinating discussion that I was delighted to have. Ever since first seeing this film at Sundance I’ve been so anxious to talk about it, and get people to see it, and promote it. I was also looking forward to meeting and speaking with the person behind it, Jesse Moss, the one-man-show who filmed and created and brought us this extraordinary documentary. So here we go… Watch the trailer/read my review.

I started the discussion by referencing Sundance, where I first caught the film (review), and how it was well received. Whenever I would ask others the best films I should see, The Overnighters was often mentioned.

What do you make of the reaction from Sundance and the buzz the film has received now?

Jesse Moss: We just didn’t know what the film would be or if people would respond to it. It’s very surreal when people say, «Your film has buzz.» You kind of just don’t believe them. You think, «Well, every film has that.» And it takes about a week to realize that’s maybe not true and maybe people really are talking about our film. All that I had to go on was my conviction in Jay and in the story, which I felt was powerful. And it moved me. And that’s the only yardstick I had. And I had the conviction of my collaborators, but they were few in number. To Jay’s credit, too, he had to make a leap of faith to come to Sundance.

I said, «Jay, I don’t know how people will respond to this film, but I believe there’s a powerful message here that will resonate and that people who don’t know anything about North Dakota will be interested.» I said, «I can’t be sure, but I think so…» That was the great revelation and surprise and affirmation of Sundance – I think it moved people in the way that it moved me. And people connected with Jay’s struggles. Because I struggled with that making the film. I went out there to make what I thought would be a movie about oil in North Dakota. And you have somewhat of a mental image of what that is, and it’s a roughneck on a drilling rig with a big piece of pipe putting it into the ground.

Here I am with this little Lutheran church with this pastor. And I knew there was something happening. And I knew Jay was really compelling, and charismatic, and complicated. And what he was doing to help these people felt meaningful to me. But it took me a long time to really let go of that image I had started with. Right away when I got there I felt very overwhelmed by the scale of what was happening. And I knew I needed a human way in. Those are the films that made me want to make documentaries, that find a way to define the intimate & the epic, and balance the two: Harlan County USA was a formative film for me.

So, I knew when I came to the church and I met Jay and I met those men… It was just a very powerful experience to be witness to his interactions with him and to see how much that they were risking to come, what they were looking for, not just work, but redemption and salvation. Jay was totally there for them. Just the emotions that were summoned were powerful. I felt like the camera was witness to this in an unusual way. And I was witness to it. And I did recognize that the church was that prism, if you will, into the bigger story. And Jay was in the fulcrum of these forces, of the influx of migrants of men and women, thousands of them, coming in, in the local community, which was buckling under that pressure. Here was Jay, one man in the middle, kind of trying to contain it.

I thought – here’s the dramatic character/situation. I think even very early on I could see that Jay had crossed this rubicon in his life that there was no coming back from. He had made this total commitment to these people because he felt that that was right and that was just. He had left his congregation behind. They were still in the building and they didn’t know it quite yet. But I could see that. And I thought there’s no going back from this. It’s going to end not well. And he even told me that. He said, «I could lose my job.»

It seems like, perhaps, by the end it becomes a vehicle for him to wash himself of his sins, to put it in a way. It’s almost like he’s saying ‘Look. I did wrong, but I’m atoning for it through this documentary.’ My question is — did he know this, was he aware of this path he was on?

Jesse: I think that there are layers to Jay… I’m still coming to understand him and his complexities. I think there was a kind of recklessness. On one hand, a real pure expression of the Christian ethic of his actions. He lived, not just preached, but practiced to love thy neighbor, but a recklessness that seemed to put him on a ruin-ess, self-destructive path. And I wondered, kind of on a deeper psychological level, where that was coming from inside of him and his heart. And that was the mystery I think that drew me into him and that he hinted at in ways. He wanted to let me know that there was more to him than his identification of broken and burdened man. But I didn’t know that the film would unlock that mystery. I didn’t press him on it.

We came to have a very deep relationship, and we still do. But there were things that we didn’t talk about. We didn’t talk politics. He didn’t try to convert me or bring me into the church. I’m not Christian. I wasn’t raised in the church. I think we had a kind of mutual respect around some of these things. All relationships have that in a way, the sort of stated and unstated dimensions of a relationship. Some things are felt and not said. So I think the surprise to me was that the film ultimately, by happenstance, unlocks that. I happened to be there when his life came apart. And it summoned those mysteries to the surface in a way that, for me, completes an understanding of him. Not to resolve him. He’s still living his life and his journey in life will continue and perhaps never resolve as we would like it to. He still wrestles with contradictions. But I think it certainly, for me, explains his superhuman compassion for people with those burdens.

Well now I want to see where he is 10 years from now, I want to see the follow-up. If this is what he went through and now, there is so much more to him, then where is he going to be after this, years down the road?

Jesse: That was a hard question with the film—where to leave the story, where to leave him. I knew that the closure of the program was one natural ending. Then I was left with this other surprise ending, which both completes and yet provokes a set of questions. That kind of complete tragic, traumatic reversal that I think makes the film something of a tragedy.

The thing that compels Jay forward is the same kind of flaw, if you will, within him that dooms him to fail. You know, that kind of intertwined thing inside of you leads to tragedy, but it also permits him to do something extraordinary. So I knew when I shot Jay at the crossroads, that to me was the last shot of the film, and this film would leave him at the place where he meets those men at the crossroads of their lives. And I think it kind of puts the question onto the viewer: Will we accept him in his failings and his humanness? Is he good or is his he bad? Well, he’s both, like the men he helps.

I was very impressed with how close you get, not just with Jay, but with shots, and scenes, and moments where I couldn’t believe this was being filmed, that this was caught on tape. Like the City Council meeting, I’m wondering how you got all of this. Were people that open? What was the reaction like? Was it just «here I am, I’m going to do this.»

Jesse: There’s no alchemy to it, in a way. First of all, it helps to be alone and to not be a crew. I mean the camera is not small. It’s on my shoulder. It’s big, actually. So you are not unobtrusive. I think I’ve also been well-trained both in my own experience as a filmmaker and for the people that I’ve worked with in terms of just really kind of going for it and being sensitive at the same time, aggressive and sensitive.

Look. A certain amount of it is just luck, making a cinema verite film. But that was really the project for me. The first film I ever made, called Speedo, I made by myself with no money. And it’s actually kind of a similar…it’s not a similar film, but it’s about one person and his turbulent life. And we became very close. I was witness to these personal moments. There was a real freedom for me in making the film that way, and I wanted to see if I could kind of find a way to make a film that way at…you know, this is 15 years later for me. I’m older and more sedentary in my ways. And yet, with Jay I found a way to do that in a relationship and a story that compelled me to work that way.

It felt a bit an anachronistic or old fashion to make a cinéma vérité film. I feel like there’s a fashion of beautiful locked off images and poetic voiceover. And, to me the films, like I mentioned, that inspire me still are the films where shit happens in front of you and you’re there. And how do you arrange to be there? If I knew how, if I could express it I would say it. And I don’t know. I think for me it’s…

Luck…?

Jesse: It’s luck. It’s about finding somebody that lets you in and allows you to be there. And it’s about being there. And it’s about them technically making sure you get it…

It is about kind of being sensitive to people. Jay would tell me… The truly unexpected moments of the film are just as surprising to him as they were to me. You know, the reporter chasing him down the street, the woman pulling the gun, the confession at the end. These were unscripted moments that I was lucky to be present for and point the camera in the right direction. But Jay also communicated in a way that made this film more possible. He would say, «Jesse, there’s a guy in the parking lot. He’s a sex offender. I think I need to move him into my house, because he can’t stay at the church, but I don’t want to turn him out. He needs a place to stay. I think he’s a good man.» This was a conversation on the phone. I said, «Okay, hold the phone. I need to come to North Dakota. I need to be there when you do this. Is that okay?»

And sometimes there were negotiations about access to moments. Some conversations are very personal and you have to kind of put the camera down and talk about why you should be there, and make your case. It’s like you are a trial lawyer and you are making your case. And sometimes you lose and sometimes you win. Then there are the moments you are just there for.

Did you ever feel concerned or worried? Or was it a little bit more gonzo, like you are just in there and whatever happens, happens?

Jesse: I did feel like in for a penny, in for a pound, particularly at the end when the woman pulled the gun out. I was like, «I’m going to keep shooting. If my subject is going to get shot dead in front of me, then I’m going to keep rolling and I’m going to go down with him.» Like we’ve gone this far. If I had shot that scene 3 months into production and not 15 months into production, I would ‘ve put the camera down and walked away, because of my investment in him, and in this film, and in this story was not so great at that point.

Living in the church was both a form of gonzo, but also just a way to get close to the story. Something that inspired me, something we read while making this film was [George] Orwell’s Down and Out in Paris and London. I don’t know if you’ve read that book, like A Road to Wigan Pier. Orwell’s journalism about the working poor is compassionate, clear-eyed, and he was able to do it because he stayed with them. He lived in these shelters in London, and not as a stunt, but because that’s where the story was. And that’s why I stayed in the church. And I needed a place to stay. And that’s where the story was. And Jay said it was OK.

So I think you need a little bit of gonzo in film. I think back to the gun moment, I think it’s kind of a good metaphor for a certain kind of independent filmmaking, both fiction and documentary. But you have to be willing to look down the barrel of the loaded gun, because if the film is going to matter, you are going to confront those moments in some fashion. It may not be a loaded gun, but it’s going to be something.

That’s a bold claim, but nonetheless it works…

Jesse: For me it’s about risk taking. I’ve done a lot of paid work. I’ve done television work and other work where other people were shouldering the risk. But the films I’m proudest of are the films that were the hardest to make or the risks were biggest in the creative, financial, personal, emotional risks. This film really felt like it was on the knife edge of failure all the time. Back to Sundance, who gives a shit about this guy? I’m thinking, «Who cares? This pastor? Who cares?» And you don’t know. You make a cinéma vérité film about somebody no one has ever heard of, and you think they are interesting, but you don’t know.

Why didn’t any of the reporters or investigators from the town come to you, or say, «You’ve got footage of this guy.»

Jesse: I don’t think I made myself that visible. I had interactions with the paper, so they certainly knew I was spending time with Jay. But I was also spending time… there were other stories, characters, places that I spent time filming for the longest time, because I was hedging my bets. I wasn’t sure that the story that I found in the church would pay off. And also, I don’t know what they could have gotten from me that they couldn’t get from themselves, to be honest.

I feel like he’s confessing in some of your footage more than he would to the newspaper because of his concerns, which he then confesses to you, about what will ruin his image.

Jesse: Back to another one of your questions, there was a confessional nature to our relationship, or almost a pastoral relationship, which is to say that Jay was in a moment of crisis. He had very few people supporting him. I showed up wanting to document his story. We became close. And I think that he drew strength in an unstated way from my presence, from our conversations, from my willingness to document what was happening, and my sense that it was important.

I did feel like in this shitty little rec room in this shitty little church, no one is going to care, really, if this is not the history that gets written. But to me it felt–and I’m not a religious person, but it felt like sacred ground, like there was so much life in this room, in these men, in their struggles, in their pain, and in their love. I was not just witness to it, but I participated in it. I stayed there. I got to know them. I smoked cigarettes with them and I cried with them.

That seems to be an important part of great documentaries nowadays, which is what you were saying earlier. For example, the The Act of Killing as well, where the filmmaker’s relationship to the subject is incredibly important.

Jesse: I think it is, at its heart, what documentary is… I mean it’s at the heart of documentary. Sometimes it’s kind of concealed, or the mode of production, or the style, or the story may be kind of masked as far as relationships. But that is often… documentary turns on that relationship between subject and filmmaker.

Frankly, the fact that this film provokes those questions about those relationships is responsible and I think where the conversation should be, in part. I think the film has a lot of other things to say, but I think you are right. I think [the same for] The Act of Killing… I’m sure Laura [Poitras]’s new film about her relationship with Ed Snowden [Citizen Four — reviewed here]. I think that these are not things to be concealed. These are things that make documentary what’s unique about the form: those close relationships, intimacy, the filmmaker’s relationship, the set of kind of ethical questions that come with documentary filmmaking, how you draw those lines and boundaries.

This film was a quagmire of ethical challenges. You know, very, very hard, painful, difficult questions to navigate, any one of which felt like they could just detonate the whole thing. And it was really stressful to negotiate this, particularly when Jay’s life fell apart and I was not just witness to it, but really very much a part of his life at that time. The film couldn’t be considered an abstraction. It’s a part of what he’s going through and what presents a certain amount of jeopardy for him and his family as well. What do you do? You talk about it. Jay and his family, they are exceptional communicators. We had probably a four-or-five-month conversation about the film between the time that I filmed the last scenes and the time the film came out into the world, about the film, about what ‘ought to be in the film, and those questions.

From a filmmaking perspective, aside from Jay Reinke, do you find that having the camera [on your shoulder] makes people open up more, or feel more closed off?

Jesse: I think what was great about Jay is that he is a natural. In documentaries you really need naturals… You can’t really convince somebody or persuade somebody to be natural in front of a camera. You either are or you are not. It’s not that Jay played to the camera. Jay just is Jay. He’s a pastor. He’s kind of a performer. He’s used to kind of holding our attention and being up on stage. He admits to that, his own ego and vanity, and how much of this project was about that attention, and was it OK that the camera was telling his story and not the story of the men?

But I knew the camera loves Jay. I could see that. And that’s OK. Jay has those layers. He’s a performer. Not just a performer to the camera, but a performer. That’s okay. Documentaries need performance. And performance isn’t a dirty word. It means that the director has to recognize the layers. Whether you are directing fiction with actors or making documentary film, in the edit room you sort of confront your subjects again in their footage and you have to look at the way people act and behave in certain scenes and say, «Well, does this feel truthful? If not, what does that mean in this film?» It’s not to say a moment that feels untruthful can’t be in the film. You just have to recognize it for what it is.

To give you an example with Jay, he cried a lot. It’s one of his strengths, frankly. He’s very, for a man, very expressive emotionally. Sometimes he would cry and I would think: «Crocodile tears. I don’t believe those tears.» I had several, many scenes of him crying. I thought, «In this film when he cries, he needs to mean it.» And when the program closed and he says goodbye to the men, he meant it and he felt it, and I felt it. We saved Jay’s tears really for that moment, when I think he feels it. And I think if you spend it too early with your audience, you lose your audience. You lose their sympathies for this person.

Is there a real message or something you wanted to say with this documentary? Or is it really just that, as a documentary, it’s about how everyone else reacts to it? Or is there really a message deep down you wanted to get out there?

Jesse: I didn’t start with a message. I found a message. The message resonated with me. And the message is: Jay’s struggle. What does it mean to love your neighbor? It’s a question we all wrestle with, whether we’re Christians or not. Particularly now in this country and this social inequality that we see in our own lives and in the country as a whole, the decisions to help people are never easy. That’s what made Jay’s struggle such a kind of universal moral struggle. It takes away from his family. It takes away from his congregation and his neighbors. You can’t give to him without taking from her.

I think that’s what the film is about. It’s not strictly a film about the oil boom. It’s not strictly about faith. It’s not strictly about all these other issues in the film. To me it’s, at its core, about compassion and about that struggle to help people. It illuminates what it truly means to love your neighbor. I think loving neighbors who are ex-convicts, and roughnecks, and these men was a kind of Christ-like test for Jay. It’s what makes him dramatic in the film. But it’s not purely Christian. It’s really human.

I agree. I think it touches upon a number of subjects. I appreciate how much it represents in how timely it is, but is also a film that shows so much more about humanity and about our culture in a timeless way.

Jesse: I liked that it was both timeless and timely. It echoes The Grapes of Wrath and the Okie migration. It echoes these frontier stories, which is the American narrative. And yet, it’s utterly of the moment about oil and energy in America today and the creation of jobs and opportunity, and the fact that the working middle class, working class of America have fewer opportunities because the economy has transformed itself. What does that tell us about where we’re headed in the future?

That kind of alchemy of past and present, of mythology and reality I found very seductive. What’s been gratifying to see in the reviews this week, too, is just how people… my previous film [Speedo], people kind of struggled with it. I felt like they didn’t quite get the film I thought I was making. But I think in this film people really read America onto this story and the times we live in now. And that’s gratifying because I felt that when I made the film.

I read that you put everything into this, and there was a moment where you were concerned that you put so much this into it without knowing that it would be anything. Has the response re-inspired you? Has it motivated you to get back out there and figure out what’s next?

Jesse: In a way, yes. But on the other hand, the total sacrifice to make the film has left me feeling both renewed in my faith in documentary, which is a great thing, and the reception the film has received makes me feel renewed. And yet, when I look at the cold hard realities of the risks, it’s just: how much do you have in you? How much can I put my family through that? How much time did dad spend away from his home without a paycheck to make this film? How much pain did I put my wife through? Thank God she supported me totally, but still, there’s so much blowback in this kind of filmmaking with your life.

I said this to somebody else: I don’t know if I could make a film any other way, but I don’t know if I can make another film like this. That’s kind of the conundrum. I mean I’ll do other work in the short term while I think about it. But it just reminds me that the work that matters is the work that entails risk in its variety of forms. I just hope I can find ways to take these risks and still kind of keep my life from falling apart.

That’s a good, but anxious, way to end.

Jesse: [Laughs] I’m hopeful. And I think the great thing about finding recognition with the film, regardless of its box office performance, is just that it helps me make another film and have supporters. And that’s been gratifying is how many people have really helped me and gotten behind the film. That’s great. You included. Thank you.

A big thank you to Jesse Moss (@djessemoss) for his time, and to Matt Mazur for arranging.

Jesse Moss’ The Overnighters is now playing in select theaters from Drafthouse Films — for a full list of theaters go here. We hope you give this excellent documentary a chance, it’s modern filmmaking at its best.

Find more posts: Feat, Interview

1

DAVIDPD on Oct 22, 2014

2

John_QPublic on Oct 22, 2014

New comments are no longer allowed on this post.

Текст выше является машинным переводом. Источник: https://www.firstshowing.net/2014/interview-the-overnighters-director-jesse-moss-talks-making-docs/