’90s Week: «Fire Island» filmmaker Andrew Ahn interviews the ’90s icon about his Teenage Apocalypse trilogy and the punk DIY aesthetic of indie filmmaking.

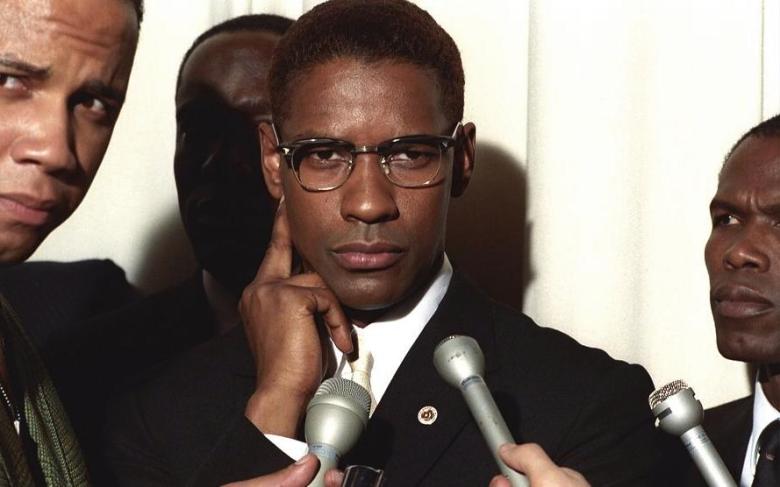

When you think about scrappy, micro-budget, guerrilla filmmaking of the ’90s, you think of Gregg Araki films. Shot on shoestring budgets with little more than his own two hands (he shot and edited his first three films, all on celluloid), Araki’s films were marked by a certain kind of radical punk rock aesthetic that mirrored the grunge era in music.

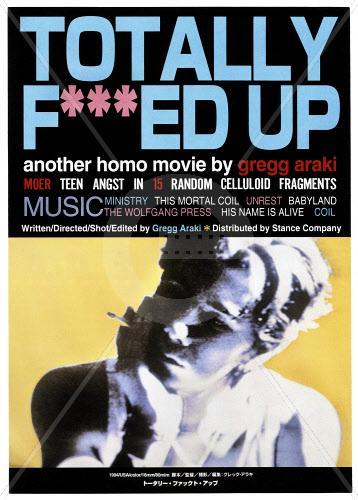

Described as a gay “Thelma and Louise,” he began the decade with “The Living End” (1992), a sexy road trip comedy about two young guys living with HIV. After making a splash at Sundance with that film, (and with the help of visionary longtime producer Marcus Hu), he churned out a trio of erotically charged teenage dirtbag films, dubbed his Teenage Apocalypse trilogy: “Totally Fucked Up” (1993), “The Doom Generation” (1995), and “Nowhere” (1997).

At the forefront of the New Queer Cinema, an enduring queerness ignites all of Araki’s films, though he certainly had fun toying with expectations. If every rebellious teenager wanted to live in a Gregg Araki film, then every promising young actor wanted to be in one. Rose McGowan, Margaret Cho, Parker Posey, Guillermo Díaz, Ryan Phillippe, Heather Graham, and Mena Suvari all showed up in the Teenage Apocalypse trilogy. And as he revealed to Andrew Ahn in an exclusive interview for IndieWire, he even auditioned — and didn’t cast! — a young Matt Damon.

Related

Related

Every indie filmmaker working today should bow down in awe at Araki’s immense oeuvre. For breaking sexual taboos, for putting dirty queer punks onscreen, and for giving a giant middle finger to the mainstream — all while making it look so sexy, so easy, and like so much damn fun.

For our special ’90s Week package, we wanted to celebrate Araki’s immense contributions to indie cinema. Though their filmmaking styles could not be more different, “Fire Island” and “Spa Night” director Andrew Ahn was the perfect choice to honor this queer film icon. In a warm-hearted discussion, the two filmmakers nerd out about cinema history, the challenges facing indie filmmakers today, and how it felt to be rocking the Sundance circuit in the ’90s.

This conversation has been condensed and edited for clarity.

Andrew Ahn: I watched your films when I was in film school, and I haven’t seen them since, so it was exciting to revisit them and be reminded of how brilliant and badass they are. There’s definitely an era that you captured, a cultural moment. You made two features in the ‘80s, “Three Bewildered People in the Night” and “The Long Weekend.” Where were you in your creative process when the ‘90s happened?

Gregg Araki: My movies were intended to be in groups of two. The first two were these black and white, 16 millimeter movies. I made them fresh out of film school. Literally, I did them by myself. I did everything. I shot them, cut the negative, edited, everything. I actually only got to make them because USC had a film lab for the student films. So they processed 16mm black and white, and that’s the only reason we could afford to do them, because they were self-financed. Those films played the film festival circuit, the gay film festivals and Locarno. So they garnered a little bit of attention and got reviews in the LA Times and everything.

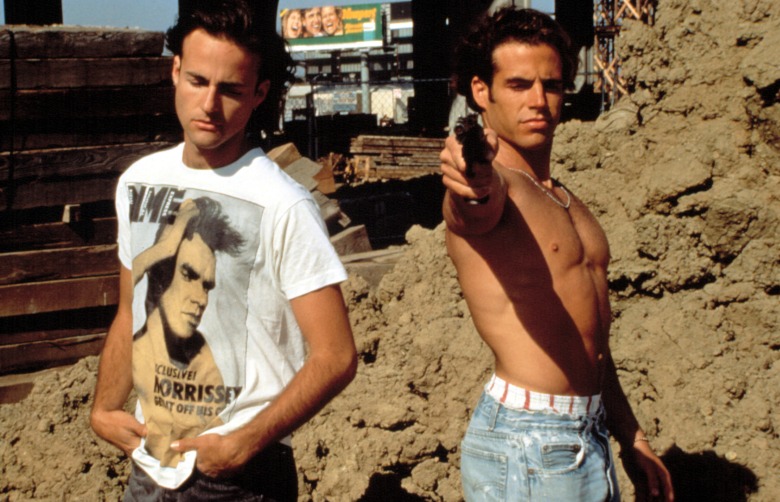

Around then is when I met Marcus [Hu, of Strand Releasing], because Marcus had seen a screening of “Three Bewildered People,” and sort of started stalking it. He said, “I want to produce your next movie.” So I said, “OK.” It was the first film I shot in 16 millimeter color with sync sound. So it became slightly bigger. The budget was 20 grand or 30 grand or something. Both “The Living End” and “Totally Fucked Up” were done in that way.

There was never a real crew. It wasn’t until I did “Doom Generation” in ’94 and “Nowhere” in ’96. Those were the movies where I actually had a real crew and a DP and 35 millimeter and a production designer and all that. They all went, in the ’90s, in sort of twos.

“The Living End”

Strand Releasing/courtesy Everett Collection

Ahn: It’s so interesting that you talk about twos, because people talk about your Teenage Apocalypse trilogy, but rewatching “The Living End” was so thrilling for me. That end shot, that end scene is so brilliant and scary, thrilling, emotional. There’s something about that film that I think captures so much so cinematically, and I love that one of the characters is a film critic.

Araki: One of the characters is a film critic, and the characters’ names are Jon and Luke after Godard. It’s full of super film school references like that. It’s all very me fresh out of film school, just being this young film school brat, very ignited with that passion of being in your twenties or early thirties and being so gung-ho about cinema and filmmaking.

It was such an innocent time. I always feel like I was born at the exact right moment. I was born in ’59, which made me in high school when punk rock music was happening. Then went to film school in the early ’80s, and I’m so influenced by punk rock music and new wave music and that whole DIY culture and not being interested in the mainstream and the corporate and what’s super popular and just being OK to be obscure and artsy and marching to your own drummer.

And then making those movies in the late ’80s, early ’90s — that’s before Sundance was really Sundance. When “Living End” played Sundance in ’92, it was after “Sex, Lies, and Videotape” but before “Reservoir Dogs.” Indie film was just sort of burgeoning. Rick Linklater is kind of the same age as me, and we talk a lot about how we had a very parallel experience. We both talk about “She’s Gotta Have It” and especially “Stranger than Paradise” was a really, hugely influential film for me and I know for Rick. “What is this fucking movie?” It was so crazy, just pretty black and white street movie. It was so arty and weird.

And it wasn’t “Black Panther,” it wasn’t a huge mainstream success. But when I saw it in a movie theater, I’m like “I can’t believe this movie.” It sparked a whole thing in me as a young filmmaker of, “Wow, you can just make this artsy little weird movie without movie stars or anything and it’ll tour the world.” But in 10 more years, it was very different. The whole landscape was different. Sundance was completely different. The whole world of indie film and indie distributors, all that was much more… I wouldn’t say treacherous, but it had become much bigger, and it wasn’t that innocent time we grew up in.

Ahn: There’s something about the pure expression that you, like your characters, have access to this artistic medium, and you can actually make something without the worry of, “Am I going to get distributed?”

Araki: Yeah, that’s the thing about those early movies. It’s mind-boggling to me that people still talk about “Living End.” It was like 30 years ago, and it was literally just this little art project that my friends did. I was just this artsy, New Wave kid from Santa Barbara who was a big Godard fan, fresh out of film school, being like, “OK, this is going to be the craziest movie.” “The Living End” was very much an expression of all of the angst and all of the feelings I was having about the AIDS crisis and the despair and nihilism of it. It was just me processing a lot of my feelings about that in a totally unfiltered and uncensored way and never thinking, “Oh, I wonder if Miramax is going to pick this film up. How am I going to get it distributed?”

And at that time in terms of queer representation, it was so shocking just to even see two guys kissing. I remember when “Living End” played Sundance, people being so shocked by it. It was so outrageous and shocking. When we remastered it in 2008, I remember watching it going, “Oh, this is actually so quaint and cute.” I mean, when they’re getting choked in the shower and stuff, there’s a little bit of that, but in general, it’s pretty chaste and pretty innocent. This was in the days before “Will and Grace,” before obviously “Brokeback Mountain” and before everything, so the idea of queer representation and queer sexuality on screen, there was so little of it. It was just really a cool time to be young and stupid and not give a shit. Although, I’m old now and I still don’t give a shit.

Andrew Ahn: I love that about you. It is such a time capsule. I was talking to my boyfriend about this and even just the emergence of PrEP makes “The Living End” feel like it’s capturing a very specific gay psychology coming out of the AIDS crisis. Maybe it feels quaint, but it also feels really important as a marker. There’s something about it that I think people will go back to in order to understand that moment in time. What was the inspiration for it?

Araki: Well, having gone to film school, I was always really into those couple on the run movies, like “Bonnie and Clyde” and “They Live By Night.” Because they tend to come out in times of socio and political stress, like the depression or the ’50s and ’60s. I was also a really big fan of screwball comedies. The structure of “The Living End” is actually taken from “Bringing Up Baby,” the Howard Hawks film. In “Bringing Up Baby,” this repressed, orderly character (the Cary Grant character) is attacked or freed by this character that represents chaos and irresponsibility. It’s a clash between order and chaos and society and this more wild, impulsive side of human nature. Playing with that structure is where the movie came from.

Ahn: I love how much of a film nerd you are.

Araki: Well, that’s the thing. My generation, like me and Gus [Van Sant] and Quentin [Tarantino] and Rick Linklater, even if some of us didn’t go to formal film school, we’re all so steeped in that language and that history. I thought that’s how it was always going to be, but apparently it’s shifted. It was just that specific moment. Again, I was born at the exact right time. Film schools really took off in the ’60s, ’70s, early ’80s. That’s when they became a real thing.

Then after that, there was this wave of… It seems that a lot of film schools and a lot of film students are less interested in film history, that history/criticism background, which is where me and my whole generation comes from. It’s more about Quentin Tarantino or Paul Thomas Anderson. It’s literally yesterday’s movies that are the big inspiration for some of the younger filmmakers.

That’s the gist of my generation. All that film history stuff, the [Alfred] Hitchcock and the [F.W.] Murnau. There’s an homage to [Sergei] Eisenstein in “Doom Generation.” Having that background and having that vocabulary has been so helpful to me as a filmmaker to be able. Not even consciously think about it, but it’s part of when I think cinematically. That’s part of the language.

Ahn: I wonder what Eisenstein would think of “Doom Generation.” That’s a fun thought.

Araki: I’m sure that he would be not happy about it.

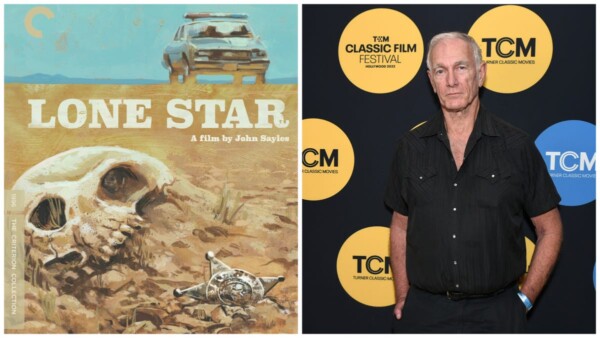

Rose McGowan in “The Doom Generation”

©Trimark Pictures/Courtesy Everett Collection

Ahn: I want to ask you what it was like DP-ing your own films. It’s a very different working process.

Araki: It was and it wasn’t, in the sense that it was a direct extension from my student films where you’re doing everything. So it was just taking that approach and continuing it into a feature. But having said that, I always hated the mechanics of it. I’m not good technically in terms of lighting and foot handles and this and that. All the stuff a DP needs to know. I’m not good at that. I loved being able to let that go and having a DP worry about it, because I used to hate worrying about, “Are we in focus? Is this the right exposure?” As opposed to just thinking about the scene, the performance, the things that as a director, you should be focusing on.

[Steven] Soderbergh still DPs his own stuff, and I don’t know why, because it’s such a relief to let that go. Because also in my early movies, I did all the production design and the costumes, everything. Just having to think about all that shit, as opposed to one person, that is their job to make sure they’re in the right costume, looking right, the collar is the right way. It’s great to have a professional do that.Ahn: I will say though, I really love the shot of Jon and Luke kissing. It’s backlit and so pretty. It’s beautifully shot.

Araki: That was one of the most fun things about making movies like that, those guerilla, handmade movies. You would get these images that were so striking and so beautiful, and so, “Wow. I can’t believe how great this looks. We did this with nothing, with our bare hands.” It’s these weird, happy accidents where you’re so amazed that the fates are just smiling on you that day.

Ahn: I want to ask you about the Teenage Apocalypse Trilogy. And I have to ask, did you know that you wanted to make a trilogy or is that just something after the fact that people.

Araki: It was very organic, because I did “The Living End” and then for “Totally Fucked Up,” I was a really big fan of “Masculin Féminin,” the Godard film. And I wanted to do a “Masculin Féminin” about gay kids. And that’s where I met Jimmy [James Duval]. I met him at this coffee shop where I used to go to write. [The whole cast] had that energy of teenage boys, and so much of that movie was just babysitting and corralling that energy all the time and it was a lot. But it was the experience of dealing with these teenagers and all their neuroses and dreams and just being around them all the time in almost a documentary kind of way that inspired me to do the trilogy.

After “Totally Fucked Up,” I decided to make these two other movies and center them around Jimmy’s character. And then in between “Totally Fucked Up” and “Doom Generation” is when I suddenly got, wow, almost a million dollars. I think it was 750k or something like that. And so it’s like, oh, there’s a crew and all this stuff.

When “Living End” came out, it was so polarizing in the gay community. People would tell me, “People are getting into fist fights in bars.” On the one hand it was such a punk rock movie and the attitude of it was so kind of “fuck everybody,” and at the same time it was hot guys making out. And what the movie had to say was so alienating to them that people would get so passionate about it. And Jim Stark, the producer, he’d say to me, “You make these gay movies that gay people hate. They’re too punk rock for gay people and they hate them.” So he’s like, “If you make a straight movie, I’ll produce it and get you real money for it.” And I said, “OK, sure,” because fuck it. Why not? So that’s why “Doom Generation” has a subtitle, “A Heterosexual Movie.” So I made this heterosexual movie, but in a very punk rock bratty way, made it so gay.

Ahn: It’s so gay.

Araki: The subtext of it is so ridiculously gay, it’s almost camp. And that’s how the script is written. It’s just written as this super queer, ostensibly straight movie.

Ahn: When you met Jimmy, James Duval, what was it that you saw in him? Was he a bit of a stand-in for you in the film?

Araki: [Laughing] People always say that. But Jimmy is not a stand-in for me in that way that [Francois] Truffaut has a stand-in in “The 400 Blows.” I’m probably more like Amy Blue than I am the Jimmy Duval character. Particularly at that time, I was very kind of punk rock and very “fuck everybody.” I always say there’s a bit of me in all those characters. Because Jimmy’s Asian looking or whatever, people think he’s me. But the Jimmy Duval character, particularly in “Doom Generation,” is so wide-eyed and innocent. I was naive and innocent in that time, but not in that way. I mean, he was literally just kind a lost lamb in the world.

Ahn: I do appreciate that he holds so much desire in “Doom Generation,” and there’s something about what he’s desiring and how we desire him that [makes him] our way into the film. Amy Blue is more of the spectacle and not necessarily the conduit for an audience. So, there’s just something about the way you’ve used Jimmy in your films that it feels like there’s something about it.

Araki: He’s kind of the soul of that trilogy in a way. Part of the inspiration for the Teen Apocalypse trilogy was meeting Jimmy and just seeing this generation. Most of the kids in “Totally Fucked Up” were straight. But this is in 1991 we shot that movie, so it wasn’t 2022 where it’s like everybody’s queer. This was a long time ago when homophobia was still really real. But these kids were just open to it and it was hopeful. Hanging out with these kids and this generation that Jimmy represented to me was how the trilogy came about.

That sort of culminated in “Nowhere,” which was this forward-looking thing where all the kids are, whatever they are. It was literally this whole, thousands of these kids who were all young and beautiful and not gay and not straight and all this music and it was just this kind of utopian world and that to me is where the trilogy was sort of headed.

Ahn: I could tell with “Nowhere” that the cast really trusted you, and also were having a blast with each other. It’s a small part, but I really love Guillermo Díaz in that film. It’s so interesting how many careers that film launched, so many amazing actors coming out of it.

Araki: Well, whenever you make these movies with young people, every season there’s a whole crop. I remember looking at the casting sheet for those, Matt Damon, all these fucking people came in and didn’t get cast, that whole generation. They all came in.

Ahn: You didn’t cast Matt Damon in “Nowhere”?

Araki: He was not cast. He didn’t make the bar, so.

Ahn: The time between each film was actually pretty minimal. What was happening between movies? Did you have a break? Did you work straight through?

Araki: It was very ‘90s. And I was younger too and full of energy. As soon as “Doom Generation” was finished, I’d already written “Nowhere.” So they all happened on top of each other but that’s, you’re always supposed to have your next thing ready. When you go to Sundance, you have your next project. OK, here’s my next, let’s do this one.

Ahn: It’s such an impressive stretch of amazing films and productivity that it hurts my brain thinking about.

Araki: But again, it’s the time. I mean this was in the wake of the ’70s, [Rainer Werner] Fassbinder used to make a movie every six months. Literally, there’s a stretch in the ’70s where he’s making two movies a year, I remember me and Rick Linklater were talking about it. It’s just like, I feel fucking lazy. There was a level of just bam, bam, bam, bam, bam. I mean, Fassbinder died of a coke overdose over 37 or whatever so it’s understandable. But [Pedro] Almodóvar used to make a lot of movies, too. These people in that time, maybe because the mechanism of it wasn’t so complicated, but there was this level of productivity that’s different now.

Ahn: I want to ask about in the ’90s what your community looked like, what your friend group looked like, was it filmmakers?

Araki: One of the coolest things about that period being in the festival circuit internationally. The Munich Film Festival had an American indie section. I met Gus van Sant at the Torino Gay Film Festival in Italy. And Sundance of course was a huge festival where I met Todd Haynes and Christine Vachon. There’s this circle of us. It’s not like we would call each other up, but we just have a thing because we’re the same, we’re kindred spirits. That’s where I met Gus and Rick Linklater and Allison Anders and Tom Kalin. It’s not like you talk to them all the time, but they’re in your circle.

So it’s always fun to be like, “Oh wow, this got nominated for an Oscar.” You keep tabs on each other and see each other around. Again, we were making so many movies that we would be on the circuit at the same time. It’s like you would finish a movie and then you’re on the circuit with the next movie and they’re on the circuit with their next movie. So you see them again at Sundance or whatever, so there was a lot of that.

Ahn: I’m very curious to know how you look back on the ’90s, now that you’re having to reminisce about it. Do you look back on it with fondness?

Araki: I look back on it with pure fondness. Maybe every generation’s like this, but things are so fucked up right now. With Trump and Roe v. Wade and all this fucking shit, the ’90s seem so innocent and utopian. I mean there was bad shit in the ’90s, I mean, “Living End” came out of the Reagan years and AIDS and ACT UP and all that stuff. So there was definitely bad stuff, but the level of shit now and all the disinformation and chaos of the post-Trump world, it makes me so nostalgic for the ’90s. I feel like it was such an innocent time and such a great time to be creative and be an artist and express yourself and not have to worry about DeSantis and the Don’t Say Gay law. It’s always been there. Maybe it’s just in retrospect it seems better, but it just seems really gnarly today.

Ahn: There’s something about hearing you talk about all this that makes me wish I could have been a filmmaker in that era.

Araki: Like I said, I was born at the exact right time. If I was born too much earlier, there wouldn’t have been the independent film world. It would’ve been in a way, John Waters. He was the generation before us and he’s the one that sort of set the path. But there was no Sundance when “Pink Flamingoes” came out, you know what I mean? He had to forge his own path and he did, thank God. But there wasn’t the apparatus for it, there wasn’t the attention, there wasn’t Sundance, there weren’t the critics. And then being born too late, once you’re in the post-Quentin Tarantino world, everything’s different. So it does feel like the sweet spot. And again, because I’m so interested in music and so influenced and inspired by music, my whole work aesthetic comes from punk rock music and that attitude of not giving a shit and doing your own thing.

This article was published as part of IndieWire’s ’90s Week spectacular. Visit our ’90s Week page for more.

Sign Up: Stay on top of the latest breaking film and TV news! Sign up for our Email Newsletters here.

Текст выше является машинным переводом. Источник: https://www.indiewire.com/2022/08/gregg-araki-punk-cinema-queer-90s-1234752647/